At 1:45 p.m. on Tuesday, May 10, 1892, an explosion and fire killed 45 miners in the Northern Pacific Coal Company’s No. 1 mine at Roslyn, located in the eastern foothills of the Cascade Mountains in Central Washington. It will prove to be the worst coal-mine disaster in Washington state history.

Kittitas County Coal

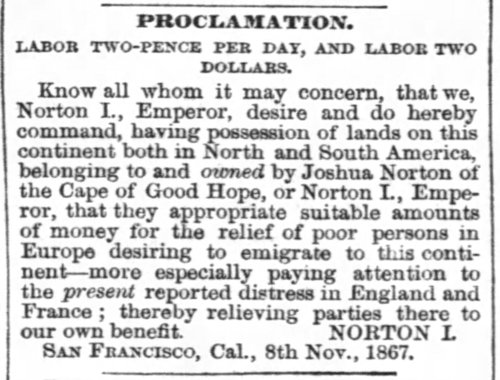

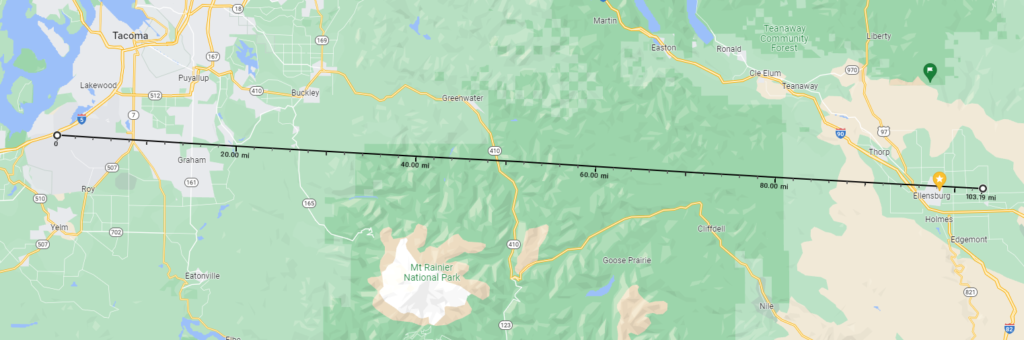

In May 1886, surveyors from the Northern Pacific Railroad found coal deposits on railroad land east of its new station at Cle Elum. The railroad needed coal to fuel its locomotives as it worked to complete the line across the Cascades through Stampede Pass. Workers immediately began to construct a rail line from Cle Elum to the new settlement of Roslyn, along with houses and mine works.

In December 1886, the first coal was shipped out of the Roslyn No. 1 mine. Roslyn — named by Northern Pacific Vice President Logan M. Bullitt either for a town in Delaware, the birthplace of a sweetheart, or for a town in New York, the residence of a friend — grew to more than 1,200 residents including many immigrants and African Americans. Roslyn No. 1 mine was followed by three more Northern Pacific mines in the area.

Conditions in the Mine

By 1892, Roslyn No. 1 mine had expanded to seven levels and a depth of 2,700 feet below the town. Eleven furnaces burned around the clock to create drafts to ventilate the mine and disperse dangerous methane gas (called at the time firedamp). But the main airway did not extend below the fourth level. A passage cut into the slope below the fourth level provided some ventilation. Miners were in the process of connecting the airway from the fifth level to the sixth level and downward when the volatile gas detonated.

Mine officials started a recovery effort, but many miners were reluctant to go back down into the mine. The first day, workers removed 14 bodies. All 45 bodies were removed by Thursday afternoon. The victims were buried in local cemeteries, one for whites and one for African Americans. These coal-mine workers were some of the 50,000 coal miners killed on the job in the United States between 1870 and 1914.

Investigations

Two committees, one of mine officials, one of miners, as well as a State Coal Mine Inspector, First District Coal Mine Inspector David Edmunds, launched investigations. The miners’ committee differed on the seat of the explosion. The company committee set the location at the airway being driven between the fifth and sixth levels and stated that the explosion was touched off by blasting powder used to break the rock. The State Inspector of Mines believed that the mining blast opened a crack to a pocket of gas and that a miner’s lamp on the slope side set off the explosion.

Most miners worked with the help of light from open flames attached to their hats. The miners on the airway side used gauze safety lamps. Coal itself contains methane and in a dusty mine an explosion immediately distills more gas from the coal dust, fueling the fire. Later coal mines were sprinkled with water to control dust, and later still they were rock-dusted (usually with powdered limestone), to dilute the highly combustible coal dust. Sprinkling or rock-dusting greatly reduces the danger of explosion and fire, but this was before that time.

At Roslyn No. 1, workers not killed by the explosion itself were quickly asphyxiated. The coroner’s jury established that “the death was cause by an explosion of gas caused by “deficient ventilation” (Inspector of Mines, 15).

The disaster created 29 widows and 91 orphans. Some families filed suit against the Northern Pacific Coal Co. The parties settled with $1,000 going to each widow except where there was a working age son and then the payment was $500.

The last Roslyn coal mine closed in 1962.

The Victims

The 45 killed miners were:

- Joseph Bennett

- Dominio Bianco

- John Bowen

- Thomas Brennan

- George Brooks

- Joseph Browitt

- Henry Campbell

- Tobias Cooper

- Joseph Cusworth, Jr.

- Joseph Cusworth, Sr.

- Herman Daister

- Phillip D. Davis

- Andrew Erlandson

- George Forsythe

- Richard Forsythe

- John Foster

- Scott Giles

- Robert Graham

- William Hague

- Mitchell Hale

- Frank Haney

- John Hodgson

- Thomas Holmes

- James Huston

- Elisha Jackson

- John Lafferty

- J. D. Lewis

- Preston Loving

- John Mattias

- Daniel McLellan

- James Morgan

- George Moses

- Benjamin Ostliff

- William Palmer

- William Penhall

- Leslie Pollard

- David Rees

- Thomas Rees

- William Robinson

- Mitchell Ronald

- Robert Spotts

- Winyard Steele

- Jacob Weatherley

- G. M. Williams

- Sydney Wright

Sources:

“Fifty Probably Killed,” The New York Times, May 11, 1892, p. 5; “The Dead at Roslyn Mine,” Ibid., May 12, 1892, p. 5; John C. Shideler, Coal Towns in the Cascades: A Centennial History of Roslyn and Cle Elum, Washington; (Spokane: Melior Publications, 1986); Annual Report of the Coal Mine Inspectors of the State of Washington, 1892, 1893, 1894 (Olympia: State of Washington, 1894), 8-16; Priscilla Long, Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America’s Bloody Coal Industry (New York: Paragon House, 1989), 24-51.